November 18, 2019 – Despite heavy investor demand, a Canadian IPO was recently scrapped due to a private equity firm impeding the process and acquiring the company at a substantial premium prior to its public market debut.

Typically, one thinks of private equity firms as astute buyers who are highly discerning on price. Ergo, investors were surprised when the private equity firm thwarted the IPO of this well-regarded private REIT by paying a record high valuation for the trust. After pricing its IPO at $15.50 – $16.60 per unit, the REIT chose to cancel its IPO and sell to a private investment firm at $20.10 per unit instead. This price represented a premium of 21% – 30% to the soon-to-be public share price before the stock was even able to trade. Not only was the premium price surprising, but the buyer paid a shockingly low 3.5% capitalization rate, representing a record high valuation for Canadian real estate assets. Why did the REIT sell to a private equity buyer instead of going public? They “gave us an offer that was so superior that we had to say yes,” the CEO of the REIT said.

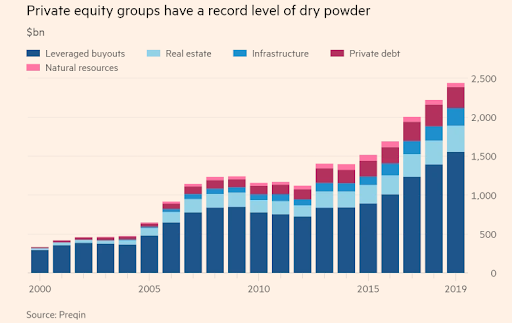

The flood of capital into private equity over the past decade has been stunning. Private equity has become so popular that the industry now has a record $2.5 trillion of unspent capital. There is so much capital in the asset class that private equity firms now own 8,000 American companies, double the number of publicly-traded companies on American exchanges.

Source: Financial Times

This $2.5 trillion of dry powder in private equity is committed but unspent capital, in which private equity firms can’t earn their substantial fees on until the money is spent. Effectively, there is $2.5 trillion of upcoming forced buying, as these firms are well-incentivized to put this money to work. A dollar not spent is a “2 & 20” fee not earned.

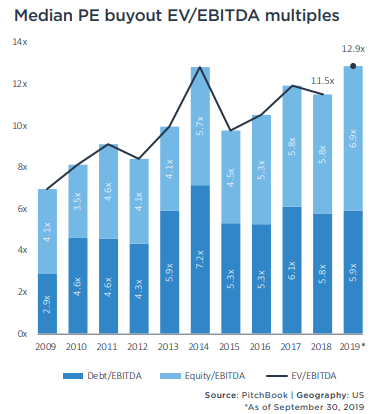

What do you get when you have thousands of private equity firms engaged in a ruthless competition of forced buying? Record prices at record valuations:

Source: Pitchbook

Ten years ago, buyouts were completed at 7x EBITDA on average. These days, buyouts are being done at nearly 13x EBITDA, a record high buyout valuation multiple. And the 13x EBITDA of the average is a very generous number. This is typically a multiple of adjusted EBITDA, which takes into account a significant number of add-backs, such as estimated future cost cuts. The true average private equity buyout EBITDA multiple is substantially higher than 13x.

The reason that rising LBO multiples is disconcerting for private equity investors is that valuation is the main determinant of future returns.

“Success in investing is not a function of what you buy. It’s a function of what you pay.” – Howard Marks

The gold-plated reputation of private equity and the insatiable demand for buyout investments from institutional investors is based off of the private equity industry’s historical returns. However, those returns were generated when valuations were nearly half of what they are today. This is problematic.

The Greatest Leveraged Buyout of All Time

A prime example of how a discounted valuation combined with copious amounts of leverage can lead to jaw-dropping investment returns was seen with the 1982 leveraged buyout of Gibson Greetings. This deal is recognized as one of the most successful private equity deals of all time. The LBO operators, former US Secretary of the Treasury William E. Simon and former New Jersey Nets owner Ray Chambers, along with some other investors, put up $1 million of their own capital to acquire Gibson Greetings for $80 million. They managed to finance nearly 99% of the deal with debt.

Simon and Chambers were able to acquire Gibson at a discounted price from the RCA Corporation, as Gibson was a small, non-core and disregarded subsidiary of the conglomerate. This discounted price reflected the illiquidity premium, a well-worn private equity mythology that is examined later in this post.

By the time the two took Gibson public just 16 months later, a combination of improved fundamentals and multiple expansion (going from a discounted valuation to a market multiple) led to a valuation for Gibson of $290 million, a nearly 4x increase. Because the Gibson deal was leveraged 100-to-1, Simon and Chambers made over 200x their money in less than a year and a half. This equated to an IRR of around 14,000%!

In the eyes of allocators, the success of the Gibson deal and several subsequent LBOs cemented private equity as a perennial and near-guaranteed market-beater.

A Primer on Liquidity

There is a persistent misunderstanding of the notion of liquidity, along with the illiquidity premium, that deserves some attention.

On the concept of liquidity, many market participants mistake trading volume for liquidity, which is generally an incorrect assumption. Just because something doesn’t trade often, or isn’t marked-to-market, doesn’t mean it is illiquid. An ETF with a $10.00 NAV can have no trades, but $1 million bid at $9.98 and $1 million offered at $10.02. It’s had no trades but it is liquid because counterparties are there ready to transact and therefore the security is marketable. Similarly, a supposed “illiquid” asset deemed so because it is a private company could in fact be incredibly liquid. Let me explain.

For example, say an LBO shop has a $20mm EBITDA midwest manufacturer in their portfolio. Given that the private company does not trade on an exchange and does not have a daily quote, many would automatically deem it as illiquid. However, if the LBO sponsor were to hire an investment bank to shop the company, there would likely be over 200 “leading” middle-market private equity firms along with strategic acquirors looking at the asset and probably over 30 bonafide bids. An asset with 30 marketable bids from the world’s most sophisticated investors armed with a tidal wave of money that they absolutely have to spend classifies as a highly liquid asset in my opinion.

Just because an asset isn’t listed on an exchange doesn’t mean it’s illiquid.

If one were to sell a non-listed asset and get full value (compared to public comparables), this is proof that the asset is truly liquid and that no illiquidity premium exists.

What is the Illiquidity Premium?

The illiquidity premium is the extra return an investor receives due to the underlying asset’s lack of liquidity (the owner isn’t able to sell it easily).

Where does this illiquidity premium come from? It is manifested through the discounted price in which a buyer is able to acquire the illiquid asset. Contrary to popular opinion, a non-traded asset does not automatically earn an illiquidity premium just because it’s private. This premium return comes from the seller accepting a discounted price due to lack of marketability of the asset. This factor premium is closely related to value, referring to the notion of acquiring an asset at a discounted price.

We see the illiquidity premium demonstrated in many asset classes. In my many years as an arbitrageur, I learned to love micro-cap merger arbitrage investments as they offered higher returns than the large-cap liquid deals. A merger arbitrageur was rewarded with an illiquidity premium in the micro-cap space because if the deal failed to close, you’re stuck with the position.

The illiquidity premium is also observed in the fixed income space. For example, say a corporation has two issues of bonds. These bonds have the same credit rating. But one bond issue is $5 billion in principal with a myriad of bids and offers in the market while the other bond issue is only $100 million in principal and is no-bid. Even though the bonds offer the same credit risk, an investor is likely to obtain a higher yield (i.e. buy at a lower price) by owning the smaller bond issue, an example of the illiquidity premium in action.

The (Lack of) Illiquidity Premium in Private Equity

Assets invested in private equity have hit nearly $6 trillion, a new record. This substantial asset base is spread over nearly 16,000 private equity firms. You can bet that most, if not all, would consider their firm as “leading” and highly sophisticated.

With the flood of capital entering the asset class, combined with the intense competition amongst thousands and thousands of sophisticated firms, it’s no wonder these dynamics have had significant effects on the market for private assets.

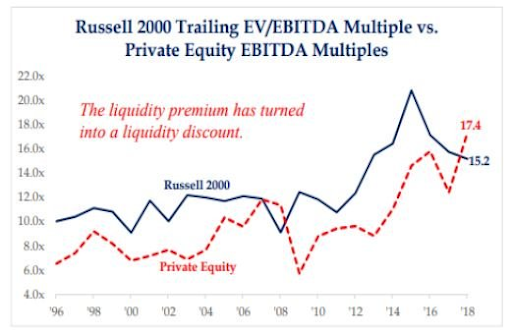

Historically, private equity firms were able to acquire assets at a discounted multiple to the public market. They typically paid below 8x EBITDA while public market comparables traded at 10x – 12x EBITDA.

If a private equity firm sought to consolidate an industry, acquiring a number of companies in a sector at 6x EBITDA, then taking the consolidated entity public at 10x EBITDA, then the private equity fund would earn an attractive return through multiple re-rating from 6x to 10x, a 67% lift. In this example, the private equity firm harvested the illiquidity premium in which they could buy private assets at a discounted valuation compared to their liquid market brethren. This used to be a key driver of private equity returns, however it is no longer the case.

Source: Strategas

The historical existence of the illiquidity premium is shown in the graph above as the spread between the red line, private equity buyout valuations, and the blue line, the Russell 2000 multiple. Throughout much of history, private assets traded at a 2-turn discount on average versus public market comparables.

Due to the flood of capital and increased competition in the private equity space, the historical valuation relationship between private assets and public stocks has flip-flopped. Private assets have gone from trading at a consistent 2-turn discount, based on EBITDA, to now trading at a premium to public market assets. According to Strategas, currently the average buyout multiple is 17.4x trailing EBITDA, which is 2.2 turns higher than the valuation of the average Russell 2000 constituent at 15.2x. Note that Strategas’ buyout multiple of 17.4x, based off of real trailing EBITDA, which is significantly higher than Pitchbook’s 12.9x average buyout multiple based off forward-looking adjusted EBITDA, a much more generous figure.

Regardless, the illiquidity premium has now reversed and turned into the illiquidity discount. This means that private assets will likely have lower returns than public assets on a go-forward basis.

The Volatility Premium – A New Risk Factor!

We have established that despite allocators’ belief that private equity is a panacea and will continue to generate market-beating returns in the future (the disclaimer that past performance is no guarantee of future performance apparently does not apply to PE), private assets are likely to generate below-market returns in the future given their premium valuations.

Given the premium valuations of private assets, public market assets are now priced attractively on a relative basis.

Consequently, with the reversal of the illiquidity premium, public market investors are now rewarded with a risk premium for holding public market assets. I deem this new risk premium to be the “Volatility Risk Premium”.

The volatility risk premium refers to the premium return that public market investors will receive as compared to private market assets, manifested through the discounted valuation of public equities compared to private assets.

What’s the thesis behind the existence of the volatility risk premium? In contrast to the private market allocators, public market investors must be compensated for tolerating daily mark-to-market volatility of their investments and the inherent career risk that accompanies it.

Mark-to-Model and Career Risk

Imagine you had to take a test, and if you scored below the average, you’d fail.

Now also imagine if you got to grade your own test, with zero consequence if you graded yourself generously. How would the risk of you failing change?

Private equity firms have it made. Each quarter, they get to pick whatever valuation they’d like for their portfolio companies (spoiler alert: they typically go up). In the test-taking example, they grade their scores to always be above average!

The peril of the public securities investor, who has to suffer at the hands of an unwieldy and indiscriminate stock market, is that they don’t get to mark their own tests. And because of this, they often score below average over short periods of time, the consequence of which is being fired by clients.

Because private assets aren’t traded on an exchange, the LBO sponsors have the benefit of extremely generous valuation marks, in which they themselves play a key role in producing. The net result of marking your assets to what you want? Unrealistic smoothing of returns and material misrepresentation of inherent volatility and risk of private equity portfolios.

One bad month can be cause for an investor redemption, cancellation of a commitment, or even an end to a career for an investment manager of public securities.

Conversely, private equity firms can just paper over the temporary losses, as the average private equity fund literally has holdings that often go to zero (bankrupt). In fact, 20% of private equity-backed companies go bankrupt, a level 10x higher than public companies. The artificial smoothing of returns benefits the private equity firms by covering for poor short term performance (which everyone has from time to time) while keeping the limited partners oblivious to the underlying portfolio volatility.

Given the disappearance of the illiquidity premium, the leverage, combined with smoothed returns to mask the tremendous risk of that leverage, is now the key draw for investors to allocate to private equity. Hence the higher private asset valuations on a relative basis.

Compared to the private asset investor, investment managers in public securities are effectively short a put option, reflecting the career risk of any short-term blip in mark-to-market performance, which cannot be covered up by clever accounting trickery. And public market investment managers need to be compensated for that risk, hence the volatility risk premium.

Why Private Equity Replication is Superior to Traditional PE

Taking into account the disappearance of the illiquidity premium and the emergence of the volatility risk premium with the recent flood of capital into private markets, driven by career risk mitigation incentivized by mark-to-model accounting, what is an investor to do?

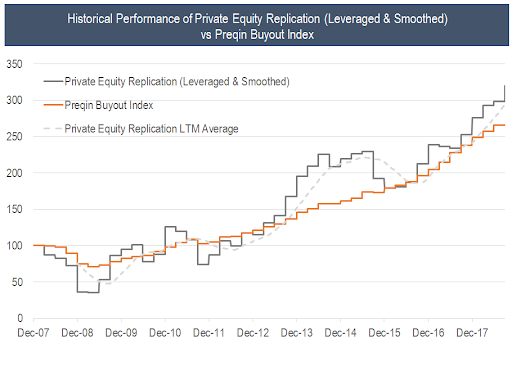

We’ve already shown that private equity returns can be replicated with liquid public securities by targeting the three quantitative factors that have historically driven private equity returns:

- Value – low EBITDA multiple stocks

- Size – small and mid-cap companies

- Leverage – add gearing to the portfolio to magnify returns

Source: Accelerate, “Replicating Private Equity With Liquid Public Securities”

The three factors that have historically generated private equity returns, value, size and leverage, are attractive characteristics for investors to target. However, they don’t need to be exclusively utilized in the private markets. In fact, superior private-equity strategy returns can now be generated in public markets.

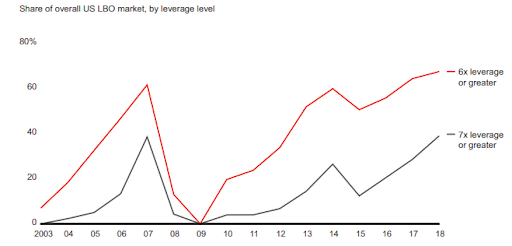

Given the record high valuations of buyouts, meaning future unlevered returns will be slim, private equity sponsors try to maintain the aura of high returns by increasing the leverage levels of their portfolio companies.

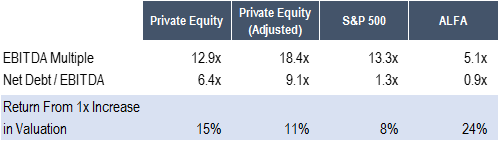

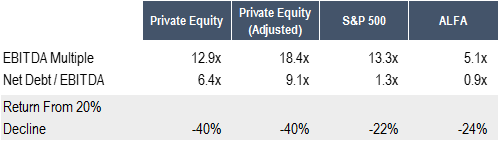

Nearly 70% of US buyouts are leveraged at 6x EBITDA or greater, and the average leverage of buyouts is 6.4x EBITDA. This compares to the S&P 500 net debt level of 1.3x EBITDA.

Private equity leverage is high, but this isn’t the whole story. These leverage metrics are stated on an adjusted basis, accounting for a myriad of add-backs that make the EBITDA figure materially higher than actual, along with the valuation and leverage level seem less extreme. According to an S&P study, private equity firms overstate EBITDA by 30% on average.

As valuations have soared higher and higher, leverage levels have followed and now sit at record highs.

Source: Bain

Accelerate runs a private equity replication strategy ETF, called the Accelerate Private Equity Alpha Fund (TSX: ALFA). This fund uses the 3-factor private equity model, consisting of value, size and leverage, to generate private equity-like returns utilizing liquid public securities with the benefit of daily liquidity, increased transparency and substantially lower fees.

The best part of a private equity replication strategy is the ability to harvest the volatility risk premium through public equities. There are some dirt-cheap small and mid-cap stocks in the public market. In fact, the ALFA portfolio trades at an average EBITDA multiple of 5.1x, compared to the S&P 500 at 13.3x, private equity at 12.9x and private equity on an adjusted basis (to account for the 30% overstatement of EBITDA) at 18.4x.

As discussed in the Gibson Greetings LBO example, private equity returns are typically generated from multiple re-rating. The lower the entrance multiple on an investment, the higher the return, in general. That is, buying an asset at a discounted EBITDA multiple, then selling it in the future once the multiple has risen, will generate great results. There are a number of paths that can lead to a company’s multiple re-rating, such as negative sentiment turning, a poor economy improving, or outright arbitraging the multiple between private and public markets (what used to happen when you IPO’d a private company to where its publicly traded comparables had a higher valuation).

This re-rating effect is most beneficial when the multiple is low (i.e. when the asset is cheap).

For example, say sentiment improved and EBITDA multiples re-rated 1x higher. This would result in an increased equity value of an LBO of 11-15%, while the equity index would only increase 8% due to its lower level of leverage. However, the ALFA portfolio, even though it has substantially lower leverage, would see it’s equity value increase 24% due to the significantly lower valuation of its portfolio.

The fact that leveraged buyout companies go bust 10x more often than public companies is reflective of the risk in private equity. This is what happens when buyout debt levels are 5x higher than that of public companies. Oddly, the Preqin Buyout Index only shows an annualized standard deviation of 9%, which is substantially lower than the S&P 500’s 15%. Something smells fishy about private equity’s mark-to-model volatility. Even worse, in the fourth quarter of 2018 when the S&P 500 dropped -14%, a private equity firm claimed its LBO portfolio declined by only -2%. Ron Burgundy best expressed investors’ thoughts regarding PE’s forgiving return profile in a down-market:

If we apply a common sense example, then it’ll show how much further a private equity fund would drop on a true mark-to-market basis during a market drawdown. The fact of the matter is a highly-leveraged portfolio of small-cap companies (a proxy for private equity) would be down substantially more than the S&P 500.

In the scenario in which multiples contracted -20%, the S&P 500 would decline -22% and the ALFA portfolio by -24% due to the modest leverage levels of these two portfolios. However, the private equity portfolios would decline by -40% (all else equal), nearly double that of the S&P 500 and an amount enough to make nearly every allocator pull their capital (if they could).

Let’s be Realistic

Clearly the fantasy of the 9% standard deviation as shown by how private equity firms mark their portfolios is pure fiction. Sophisticated investors are onto PE’s tricks, as some institutional investors estimate the standard deviation of private equity returns is 24%, while other investors estimate is to be as high as 100%. In a market downturn, one can expect the true value of a private equity portfolio (on a marked-to-market basis) to drop roughly double the equity index, so an assumption of a standard deviation of 30%, double that of the market, is fair. Note that this is over 3x higher than what the Preqin Buyout Index and the LBO sponsors’ mark-to-model valuations tell you.

The truth regarding private equity is that it is far riskier than it appears and investors should not be oblivious to this fact. On the other hand, the 3-factor private equity model – owning small and mid-cap value stocks with leverage – produces great investment results over the long term. The problem with traditional private equity is that the flood of capital has taken value out of the equation, such that leveraged buyouts are now overvalued compared to public equities. The best way to get real private equity returns is through focusing on small and mid-cap value equities, with a bit of leverage, in the stock market with private equity replication. Just buckle up your seat belt because it’s going to be a wild ride.

-Julian