April 18, 2019 – The classic thinking that many amateur investors, and even some professionals, have is that if you buy a stock with a high dividend yield, you should do well in the markets. Certainly, there is no shortage of dividend-investing hype and catch phrases:

“Income Investing!”

“Get Paid to Wait!”

Ever since the global financial crisis of 2008-2009 brought interest rates to rock-bottom levels, many investors have turned to buying dividend stocks to earn income. I mean, what could be so bad about collecting quarterly dividend cheques?

Turns out, focusing exclusively on dividends may be bad for your financial health.

Dividends Just Don’t Matter Anymore

A corporation has five main areas to allocate capital:

- Capital expenditures (“capex”)

- Research and development (“R&D”)

- Mergers and acquisitions (“M&A”)

- Dividends

- Share buybacks

The first three choices, capex, R&D an M&A, stem from the company’s decision to reinvest its free cash flow for growth initiatives.

Dividends and share buybacks, also known as “shareholder yield” when combined, are ways to return cash to shareholders. When a corporation produces excess free cash flow, it can return cash to shareholders either via dividends or share buybacks. From a corporation’s perspective, both dividends and share buybacks are the same thing except that share buybacks are a more tax efficient method of returning capital to investors.

Throughout most of capital markets history, share buybacks were actually illegal. It wasn’t until 1982, when the SEC passed a new rule allowing for buybacks, did the composition of shareholder yield begin to change.

Prior to the emergence of buybacks in 1982, dividends were important and were typically decent proxies for free cash flow of a corporation.

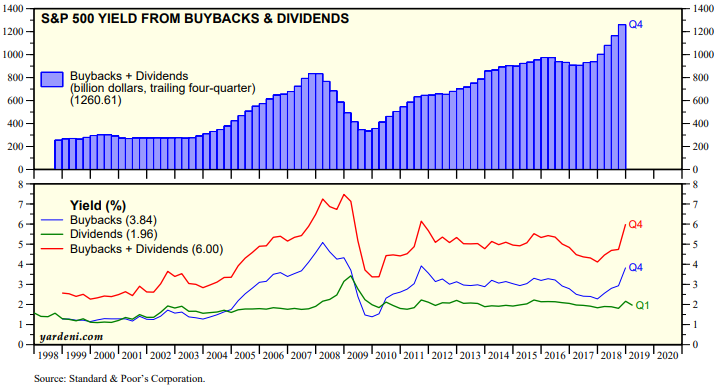

However, over the past few decades, there has been a bonanza in the growth of share buybacks. In the S&P 500 index, buybacks have become so pervasive that the buyback yield is nearly 4%, or almost double the index’s dividend yield. Buybacks now account for two-thirds of the S&P 500’s shareholder yield of 6%.

Source: Yardeni Research

The S&P 500 buyback yield has exceeded its dividend yield almost every year since 2005. Therefore, it is more important to look at share buybacks when evaluating cash payments from corporations to shareholders, as buybacks now account for the lion’s share of shareholder yield.

Easy To Manipulate

There’s a dirty little secret that many income investors don’t know:

Theoretically, a company can arbitrarily set its dividend yield, as long as it has access to cash, liquid assets or a line of credit. When a company pays out more money than it produces in free cash flow, it can fund this by partially self-liquidating to pay an artificially high dividend, at least temporarily.

Artificially high dividends are often seen in the closed-end fund space. Many closed-end funds (which shall remain nameless) set their dividend yields artificially high, typically north of a 10% yield, when the underlying portfolio only generates sub-5% dividend yields, in order to attract less sophisticated investors in search of yield. This dividend is mostly return of capital – effectively paying investors their money back as the closed-end fund slowly liquidates to fund the payments.

Artificially high dividends were once a popular business model for income trusts. Trusts used to pay distributions in excess of their free cash flow, making up the difference by regularly raising capital via equity issuance. However, raising money from new investors to pay old investors has a negative connotation to it (Ponzi), and this business model generally doesn’t last very long.

Out of the investable universe of Canadian stocks (ie. those trading above $2.00), 62% of stocks pay a dividend. However, 45% of Canadian stocks generated negative free cash flow over the past year. 19% of Canadian stocks paid a dividend while generating negative free cash flow and 34% of publicly traded Canadian companies paid a dividend last year that they couldn’t cover with their positive free cash flow.

Don’t Be Fooled By a Fat Dividend

A recent example of investors being drawn into an overvalued, underperforming stock based solely on its high dividend yield is the BP Prudhoe Bay Royalty Trust (BPT). This trust owns one asset, being a royalty from BP’s Prudhoe Bay oilfield on the North Slope of Alaska. The Trust pays a variable quarterly dividend based on the royalties it receives, which depend on oilfield production levels and the price of oil. Given the depleting nature of the oilfield, BPT expects to stop receiving royalty payments after 2022. Since dividends are be expected to cease in three-and-a-half years, it’s easy to discern that BPT is overvalued based on the present value of its expected future dividends, with the last quarterly dividend being $0.35 per share.

At the start of the year, BPT was yielding over 25% annualized, based on its Q4 dividend payment of $1.38 per share. Investors bid up the stock to a price far above intrinsic value, the present value of its future cash flows, based on this apparent juicy dividend yield.

However, reality struck when the trust announced the Q2 dividend of only $0.35 per share, which sent BPT shares tumbling -14%. Investors aware of BPT’s intrinsic value, which is relatively easy to model, would have not owned the stock and therefore would have sidestepped the carnage. Investors owning the shares exclusively for the dividend would have been shellacked.

A Poor Man’s Value and Quality Factors

The main reason we’re against investing based solely on dividends is that the dividend yield is not a robust factor; it is not predictive of excess future returns. Going long high dividend yield stocks while going short low dividend yield stocks has not historically produced alpha.

Conversely, dividend stocks can indicate a stock with a low valuation or high quality, given dividend payers typically generate positive cash flow. Dividend yield investing is really just a watered-down version of value and quality investing – and a poor one at that.

Empirical data shows that an investor is likely to earn higher returns by focusing on a stock’s valuation and/or quality, based on measures such free cash flow and return on capital, instead of dividend yield.

Let’s look at the numbers:

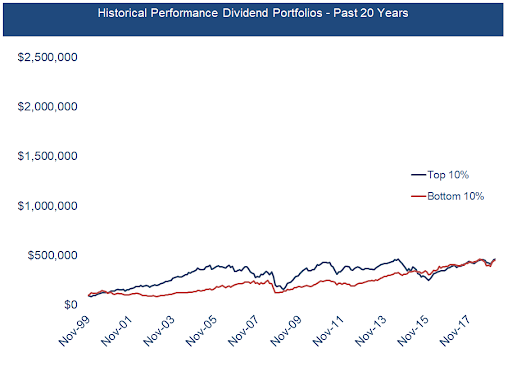

Over the past 20 years, Canadian stocks in the bottom 10% of dividend yield would have performed essentially the same as the top 10% of dividend yielders at 8% per annum. A $100,000 investment into either the highest dividend yielders or the lowest would have been worth $450,000 after 20 years.

While both top and bottom decile dividend-yielders outperformed the TSX Composite by about 1% per year over that time frame, both sets of dividend yielders got crushed by low valuation and high quality stocks.

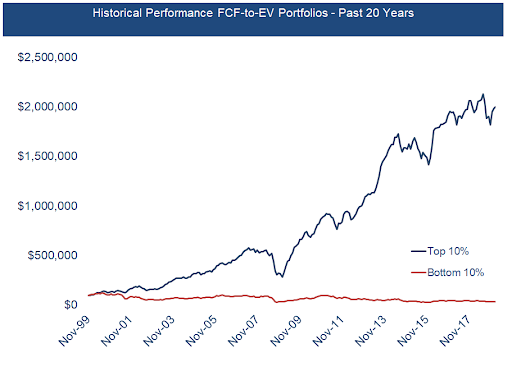

The top decile of FCF-to-EV stock portfolio, made up of stocks with low valuations based on free cash flow, would have compounded at 16% annualized, double the dividend portfolio. A $100,000 portfolio would have exceeded $2 million after 20 years. The bottom decile FCF-to-EV portfolio would have lost nearly -5% annually and a $100,000 portfolio based on the highest valuation stocks ended up at only $38,000.

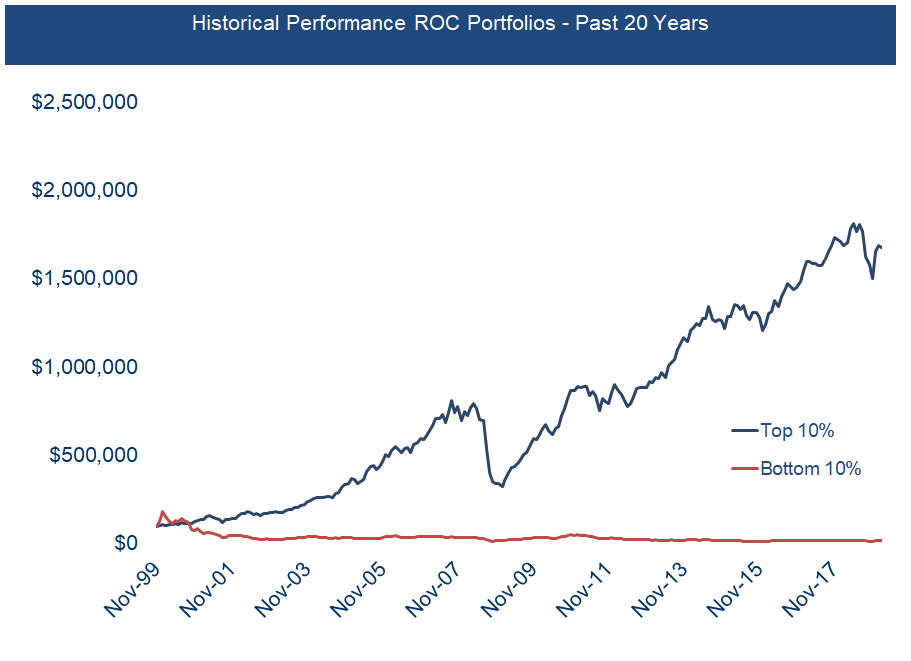

The top decile quality portfolio, made up of stocks exhibiting high return on capital, compounded at 15% per annum over the past 20 years. A $100,000 investment in the top 10% quality portfolio would grow to nearly $1.7 million after 20 years. The bottom 10% quality portfolio, made up of stocks with the worst return on capital, fell over -8% annually over 20 years and lost over 80% of the investor’s portfolio over 20 years.

In contrast to the dividend portfolios, the divergence between the top decile value and quality portfolios compared to the bottom decile really points to the robustness and effectiveness of the factors. Empirical evidence indicates that focusing on valuation and quality of securities will earn you higher total returns compared to investing based on dividends alone.

But What About My Much Needed Income?

Investors can be hurt when blindly chasing dividend yields. Instead of focusing on dividend yield, investors should focus on total return. Valuation and quality-based measures offer a better model to generate total return compared to investing based on dividend yields, as seen above.

Total return is inclusive of both capital appreciation and dividends. The “income” an investor receives should be viewed through the lens of total return. An investor can generate income by harvesting capital gains. One should be indifferent to $1 from dividends or $1 from capital appreciation. Instead of utilizing only dividend payments, investors can pay themselves out of total return. The best part of this strategy is that it’s more tax efficient, as capital gains are typically taxed at a lower rate than dividends.

Dividend Yield? Forget About It

Dividends have lost their luster ever since share buybacks came to dominate shareholder yield over the past 15 years. Combine this with the viewpoint that dividend yield investing is just a watered-down version of value and quality investing, albeit a much worse version.

If you insist on sticking with a yield-based investment strategy, invest based on free cash flow yield and quality instead of dividend yield. Your net worth will thank you later.

-Julian