April 3, 2019 – Value investing’s obituary has been written numerous times over the past decade. The reason attributed to its death is poor performance. Is this reality or is it fake news?

The Found Art of Value Investing

Value investing, the practice of buying securities deemed undervalued compared to their intrinsic value, was brought to the forefront of investment management by Ben Graham with his seminal book “Security Analysis”, first published in 1934.

Typically, stocks are deemed to be of the “value” category if they are trading at a low multiple of a certain fundamental financial metric relative to the market multiple. For example, a stock may be undervalued based on various measures such as:

- book value,

- net earnings,

- free cash flow or

- EBITDA

These metrics lead to valuation multiples such as:

- price to book value (P / B),

- price to earnings (P / E),

- enterprise value to free cash flow (EV / FCF), or

- enterprise value to earnings before interest taxes depreciation and amortization (EV / EBITDA)

Value investing has been around for nearly 100 years. Ben Graham practiced value investing in his investment partnership throughout the great depression, in which he focused on buying stocks trading for less than their net current asset value (NCAV). Graham defined the quantitative formula for buying shares of companies for substantially less than their NCAV, being the companies’ current assets less their total liabilities and preferred shares. Purchasing shares at this low valuation gave Graham what he deemed a “margin of safety”. He viewed the NCAV as the value that a company could be liquidated, or sold for scrap for, and insisted on buying stocks trading below this level. NCAV is a balance sheet valuation metric similar to that of book value.

Graham had a number of well-known disciples who went on to have illustrious investment careers utilizing his strategy of buying securities trading below their intrinsic value.

Value Gains Momentum in Academic Circles

A few decades later, academic researchers began to study these value investing techniques. Specifically, in 1977, S. Basu published a paper entitled “Investment Performance Of Common Stocks In Relation To Their Price-Earnings Ratios: A Test Of The Efficient Market Hypothesis”. This paper backtested a value strategy based on the P/E ratio, a common value metric, and found that “the low PE portfolios seem to have on average, earned a higher absolute and risk-adjusted rates of return than the high PE securities”. According to Basu, value investing worked.

In 1992, Eugene Fama and Kenneth French popularized value investing with their paper “Common risk factors in the returns on stocks and bonds”. This paper built off the findings of other studies completed throughout the 1980’s. One factor that Fama and French popularized with their research was the book-to-market value factor, or the inverse of price to book value multiple.

This value factor, book-to-market, indicated that stocks at high book-to-market (ie. low price compared to their book value) tend to outperform, while stocks at low-book-to-market (ie. high price compared to their book value) tend to underperform.

The Problem With Value

Many firms took the value factor and ran with it. The book-to-market value investing methodology proliferated within the investment community, as its noted outperformance obviously held mass appeal.

The book-to-market factor was so successful that now the top 15 value ETFs in the U.S., managing approximately $180 billion of assets, all use the book-to-market factor to some extent in their index methodologies (some based solely on book-to-market and some a composite of various value factors including book-to-market).

In fact, the most frequently pointed-to gauge of value investing’s performance, the popular Russell Value Indexes, is solely built off of the book-to-market factor.

If you ever read an article about how value is outperforming or underperforming, it is almost always referring to one of the Russell Value indexes.

The vast majority of value strategies and indexes are based on the book-to-market factor.

The problem here is straightforward: The book-to-market factor doesn’t work. It sucks and is not a good measurement of value at all. Let me explain.

A company’s book value used to be a decent proxy for its intrinsic value, but stopped working decades ago. If you ask a fundamental investor to analyze and value a stock, rarely, if ever, will they look at book value. It just isn’t meaningful anymore for a number of reasons. First, the accounting treatment of corporate actions, such as acquisitions and share buybacks, have made book value essentially meaningless. Second, the proliferation in the stock market of more asset-light, service-based businesses, which typically earn income from valuable intangible assets whose value is not properly captured in a company’s accounting measure of book value.

If book value is mostly meaningless these days, then what company metric can be used to appropriately measure a stock’s valuation?

The answer lies in cash flow, or some variant thereof. My favourite methodologies are to compare Enterprise Value to EBITDA or free cash flow. Enterprise value is superior to that of just equity market capitalization, because it takes into account the entire firm value, including debt, equity and preferred stock, rather than just equity. Cash flow measures, such as EBITDA and FCF, are better than balance sheet measures, such as book value, as cash flow values a business based on going-concern value while book value looks on a liquidation basis. Most public companies are more appropriately valued as a going-concern as opposed to a liquidation – they tend to be worth more alive than dead.

The Proof is in the Pudding

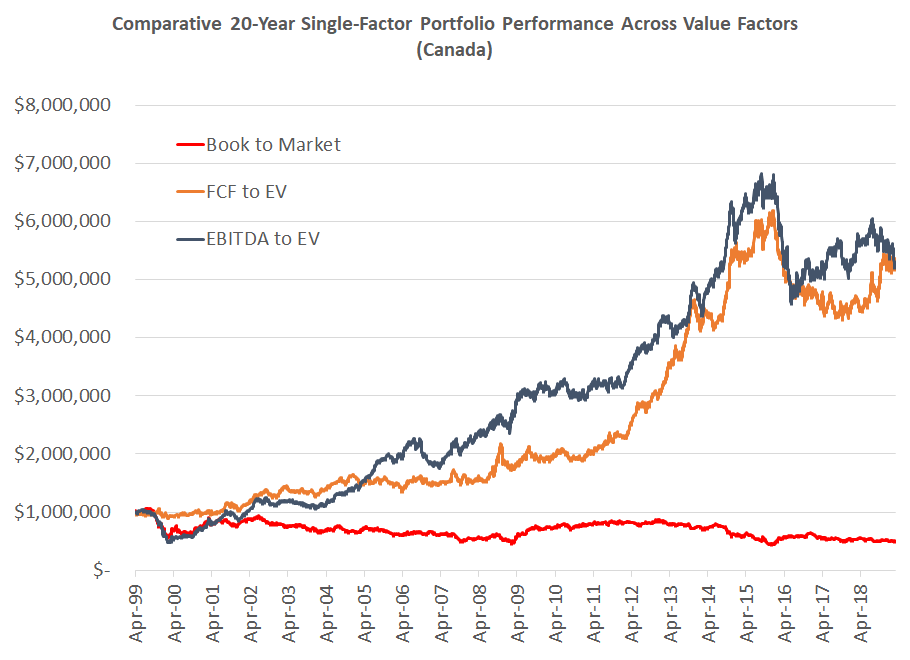

Our quantitative research team ran the numbers and compared the simulated performance of a market neutral, or a 100% long / 100% short strategy of all three value factors: book-to-market (red), FCF to EV (orange), and EBITDA to EV (blue):

Starting 20 years ago, $1 million is invested in each value factor’s long-short portfolio. These portfolios go long top decile and short bottom decile of the specific factor. This means they go long the most undervalued stocks, according to the value factor, and short the most overvalued stocks.

To make this simulation as realistic as we could, the simulations utilize a risk model and account for commissions, market impact and short borrow fees. The portfolios are rebalanced monthly.

As you can see, over the 20 year timeframe the FCF to EV and EBITDA to EV factors had outstanding performance, while the book-to-market factor had a rough go of it.

The $1 million long-short portfolio in the FCF to EV and EBITDA to EV strategies would both be worth $5.3 million after 20 years, for a cumulative return of over 400% and nearly 9% annualized.

The $1 million long-short portfolio in the book-to-market would have been halved to $0.5 million, for a cumulative return of -50%, or -3.4% annualized.

Value Investing Isn’t Dead

As you can see, value investing isn’t dead, however, book-to-market sure is. From a fundamental perspective, investing based off of a company’s book value makes little sense. Historical simulations, along with underperformance of the Russell value indexes, prove this point.

Don’t believe the fake news. Value still works and the EV / EBITDA and EV / FCF metrics are still going strong. Long live value investing!

-Julian