May 7, 2020 – Each decade is typically characterized by a financial innovation that comes to define a certain point in economic history.

The “go-go” eighties brought the high-yield bond, which powered the high-flying career of junk-bond king Michael Milken and helped bring leveraged buyouts to the forefront.

The great bull market of the nineties highlighted the exponential growth of the mutual fund, captivating retail investors and cementing star managers such as Peter Lynch and Michael Price into investment lore.

In the 2000’s, certain complex credit products such as credit default swaps and collateralized debt obligations were borne of a credit binge, of which legendary hedge fund manager John Paulson utilized to make billions of dollars betting against the housing market, setting the stage for the “greatest trade ever.”

A more pedestrian financial instrument best represented the twenty-tens, the exchange traded fund (ETF). Low-cost and easy to use, ETFs helped bring index investing to the masses, popularized by firms such as Vanguard and iShares.

What is in store for the twenty-twenties? It’s still too early to tell, so the jury is still out. However, the SPAC has made a strong case to be the defining financial instrument of the decade.

What the Heck is a SPAC?

SPAC is an acronym for special purpose acquisition company. Also known as a “blank-check company,” a SPAC is a cash-rich shell company that raises money from investors in an initial public offering and seeks to acquire a private acquisition target over a fixed time period. Simply stated, it serves as a vehicle to bring a private company to the public markets.

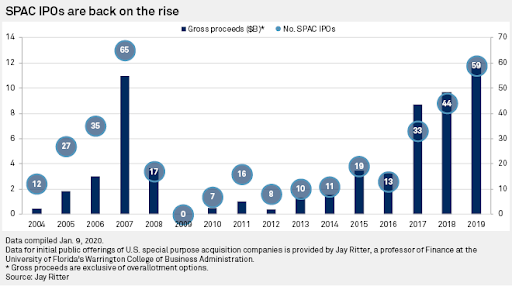

SPACs have emerged in recent years as a viable alternative to the traditional initial public offering as a way for a private company to complete a going-public transaction. Its emergence as an asset class has been made apparent by its fast growth over the past few years.

Source: S&P Global

After the economic hangover from the 2008-2009 global financial crisis, SPAC issuance was left for dead. However, over the past three years, SPAC financing has come back with a vengeance. In 2019, SPAC financings reached a record annual haul of $12 billion. Last year, the 59 special purpose acquisition company IPOs represented 25% of total initial public offerings. In the first quarter of this year, the trend continued with 13 SPAC IPOs, which represented nearly 30% of all initial public offerings.

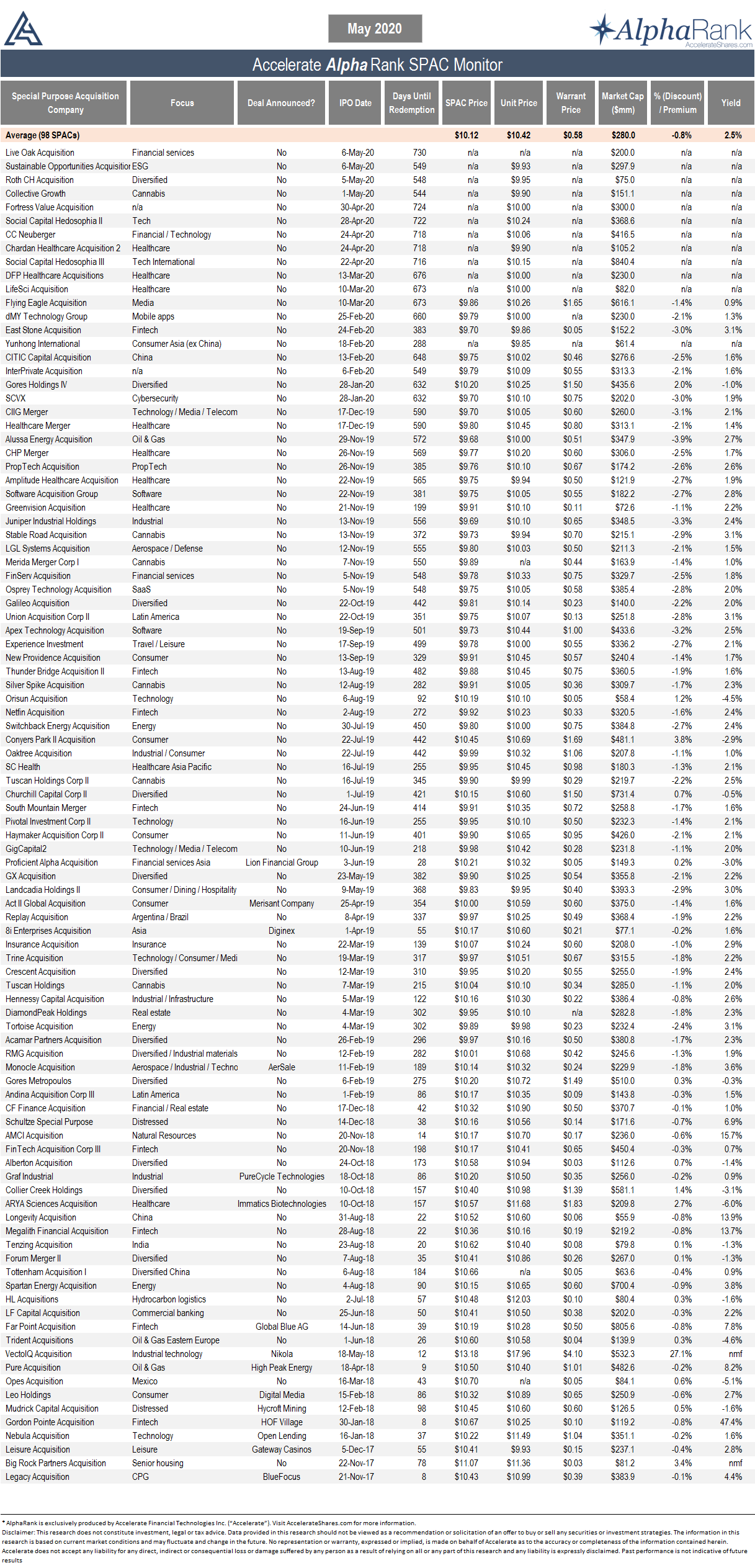

There are currently 98 SPACs outstanding representing an aggregate market value of $27.5 billion. Accelerate’s proprietary AlphaRank SPAC Monitor showcases all outstanding SPACs.

Source: Accelerate

SPACs are a legitimate, multi-billion-dollar asset class that is here to stay, while offering a unique arbitrage opportunity for enterprising investors.

How Do SPACs Work

The typical SPAC is a Delaware corporation that completes an IPO for as little as $40 million to as much as $800 million, although there isn’t a set minimum or maximum. Over the past two years, the average SPAC initial public offering has raised $234 million.

In the IPO, a SPAC offers units to investors for $10.00 per unit. Each unit consists of a common share and a fraction of a warrant. Units contain anywhere from 0.25 warrants per unit to as much as a full warrant per unit. The warrant terms are such that they offer the investor the option to buy more shares at $11.50 per share in the future (as long as five years), giving a SPAC unit investor further upside on the performance of the company.

Capital raised in the IPO is placed in a trust account, which is tightly governed. This capital may only be invested in the safest securities – typically U.S. treasuries of tenors less than 185 days. These funds cannot be used to finance the operations of the blank-check company as it searches for an acquisition target. The capital raised in the IPO remains in the trust account accruing interest and is only used to acquire a company or to distribute to redeeming shareholders. To provide the necessary working capital, the SPAC sponsor subscribes to private placement warrants, which will allow the sponsor to buy shares at $11.50 after it completes a business combination. This investment in private placement warrants represents capital at risk for the sponsor. If they do not get a deal done within the allotted time frame, the millions of dollars spent on the private placement warrants are lost. The private placement warrant financing provides working capital to the SPAC, so the IPO proceeds in trust remain untouched until the deal vote, business combination or company liquidation.

Where is the upside for the sponsor or promoter of the SPAC? In exchange for setting up the blank-check company, funding the working capital through a subscription of private placement warrants and searching for a business combination, the sponsor is given founder shares for nominal consideration. These founder shares convert to 20% of the pro-forma equity once a business combination is complete. If a SPAC fails to complete a business combination within the specified time frame, these founder shares become worthless as are the private placement warrants. There is immense financial pressure for a sponsor to get a deal done.

Generating Investment Returns from SPACs

Once the IPO is completed, the SPAC is listed on an exchange and its units start trading in the market while the company is on the hunt for a business combination. As stated in its prospectus, a SPAC has limited time to complete an acquisition – typically 12 to 24 months.

SPAC units, essentially common shares paired with warrants, trade as one security usually for the first 52 days. After 52 days, investors have the option to separate trading of the units into common shares and warrants.

The key aspect of SPAC arbitrage is the existence of untouched capital from the IPO invested in risk-free U.S. government securities, giving investors a baseline return of short-term treasury yields, combined with a set deadline offering the ability to redeem shares for the underlying net asset value (NAV, or the value of the treasuries plus accrued interest) either around the date of the vote for the SPAC’s business combination or its liquidation date.

A SPAC’s NAV starts at $10.00 upon its IPO. As time passes, the NAV grows as interest accrues. An investor can track each SPAC’s net asset value by analyzing 10-Qs, 10-Ks and proxies.

The return on a SPAC investment consists of two value drivers: yield and optionality.

Yield is measured as the accrued interest on the SPAC’s NAV, which consists of short-term treasury securities. Last year 180-day T-bills yielded about 2.5%. Now the same T-bills yield roughly 0.15%. Therefore, the baseline yield on SPACs is extremely low right now. However, additional yield can be generated by buying the SPAC in the market at discount to its NAV. Currently, the average SPAC trades at a -0.9% discount to its NAV and offers a 2.4% yield.

Why do SPACs generally trade at a discount to their net asset values? SPACs are less liquid than the underlying treasury securities, therefore, investors typically require a higher return to own a less liquid asset. This phenomenon is known as the illiquidity premium, which is defined as the premium return an investor can earn for holding an asset that is difficult to trade out of.

Optionality refers to the return a SPAC investor can attain in addition to yield. This upside can occur when the sponsor announces an attractive business combination for the SPAC. The announcement of an attractive acquisition can bring in new investors and speculators into the stock, driving its share price well above NAV.

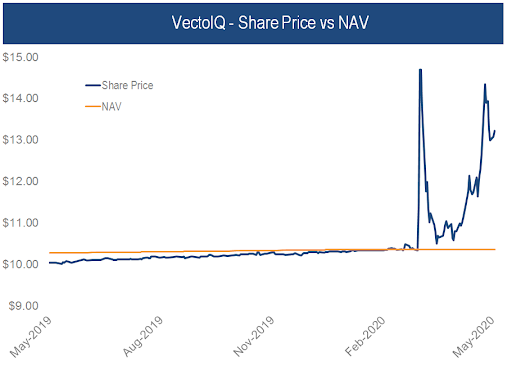

For example, blank-check company VectoIQ Acquisition recently announced a business combination with electric vehicle maker Nikola Motor Company.

Source: Bloomberg

Investors viewed this announcement positively and bid up the stock far in excess of the SPAC’s net asset value, crystalizing the upside optionality for SPAC arbitrageurs.

Three Ways to Arbitrage

There are three ways in which an enterprising investor can earn arbitrage returns from a special purpose acquisition company:

- Acquire the SPAC units, preferably at a discount to NAV, and earn a yield above treasuries. Split the units into common stock and warrants when available. When a deal is announced, observe how the market reacts to the potential business combination and compare the SPAC common share price versus the underlying net asset value. At the time of the shareholder vote, if the SPAC price is above its NAV, then sell. If the SPAC price is below its NAV, then redeem. Vote for the deal and hold onto the warrants for additional upside optionality.

- Acquire the SPAC shares, preferably at a discount to NAV, before a deal is announced. Earn the baseline yield, which consists of accrued interest on the company’s T-bills plus the return gained from the eventual closing of the NAV discount. If a positive deal is announced that takes the SPAC’s share price above its NAV, then sell and crystalize the upside optionality. If the deal stinks and the shares do not trade above NAV, redeem the SPAC shares upon shareholder vote or liquidation and close the position. If one only owns the common shares, no warrants come into play.

- Acquire SPAC shares at a discount to NAV as they head to liquidation. This is a straight rate-of-return trade, in which an investor earns the underlying treasury yield plus the NAV discount up to the SPAC’s liquidation. If a SPAC doesn’t announce a deal before its deadline, or if too many investors redeem in the case of an unattractive business combination, the SPAC will liquidate and distribute $10.00 per share plus accrued interest.

Occasionally, a SPAC bumping into its deal deadline will stage a shareholder vote in order to extend its life. Typically, the sponsor will pump in a bit more cash into the SPAC to incentivize shareholders to vote for the deal extension, giving management more time to find a business combination, and not redeem their shares. An example of this would be an extra $0.10 per share for a 3-month extension, which increases a SPAC arbitrageur’s return by 1%.

Why Investors Should Consider SPAC Arbitrage

SPAC arbitrage is one of the lowest-risk investment opportunities out there. If done properly, there is little downside risk, assuming one isn’t forced out of the position at an inopportune time.

During the recent coronavirus-induced market panic, some SPACs traded at a considerable discount to net asset value as hedge funds, who are the main buyers of SPAC IPOs, were forced to sell in order to meet client redemptions. During this period of market stress, investors could buy SPAC at a discount to their NAVs and earn near-risk-free baseline returns of 5-10% annualized, not taking into account any upside optionality.

That is equity upside combined with the risk profile of treasury bills.

Given its attractive risk-reward dynamics, enterprising investors should consider an allocation to SPAC arbitrage in their portfolios. The Accelerate Arbitrage Fund (TSX: ARB) provides investors with a diversified portfolio of SPAC arbitrage opportunities.